Behavior Curious: B.F. Skinner and His "Radical" Assumptions

Overview of the basic assumptions of radical behaviorism, as a philosophy of science (and life!)

As I mentioned, it’s hard to know where to start with all this Radical Behaviorism / Behavior Analysis (RB/BA) stuff. So many books, so many studies, nearly 100 years of history — where to start?

Here, I offered a brief recap of “behavior” and “behaviorism”, some historical context, and — the meat of the post — a lay-language overview of the philosophical foundations of radical behaviorism, followed by some resources for the super curious. I tried to keep it all non-snoozy, but this is complex stuff. Questions and comments are welcome.

Recap

In Chapter 1, What is Behavior, we covered the word “behavior” (do-say-think-feels) and, in a footnote, the complex topic of behaviorism, as a continually evolving discipline.

We established that the word “behaviorism” means lots of things — as a discipline, it branched off several times in its century of existence. I have no idea what most people think when they hear the word “behaviorism,” but I’d wager that hearing it doesn’t evoke the good feels it could. I’d really like to change that.

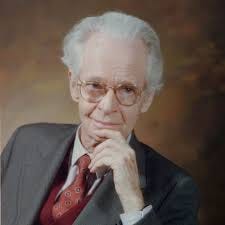

In this publication, I’m talking specifically about the philosophy and science of the most eminent psychologist of the 20th century, B.F. Skinner, and the subdiscipline of psychology he and others initiated, “Behavior Analysis.” (If you haven’t heard these words before, but you’ve heard of, say, Freud, that’s WILD, as Skinner was hands down the top contributor to psychology in the 20th century. I’m so glad you’re here.)

We also established that, in the 1920s and early 1930s, B.F. Skinner was among the people thinking “enough’s enough” to the direction psychology was headed. He was dissatisfied with how lay language and lay assumptions were driving the bus of what he thought should be a natural science, like physics or biology.

And with that recap, here we are at today’s post.

Historical Context, Minus the Snooze

OK, so, it’s 1920s/1930s. Psychology, the lovechild of philosophy and medicine, has been around for about 50 years, if you start counting with Wundt. They (psychologists) have thus far been doing all kinds of stuff, some it whacky — ids, egos, and superegos; phallic representations and dream analysis; phrenology; tons of physiological measures; intelligence tests; rat mazes; pondering about consciousness — all driven by culturally rooted inquiry and need.

In the 1920s, Skinner — originally a literature major and wannabe writer — became interested in psychology and, after a “dark year” of basically not writing (relatable, right?), he went to study under William Crozier at Harvard. (You know, like you did in 1920s America as an upper middle-class white man with decent grades and all kinds of priviledge.)

Crozier was also a bit critical of psychology at the time and encouraged Skinner to study behavior as a subject matter in its own right. He did — and then some. You can read more about Skinner’s life in this biographical info or his autobiographies.

Skinner’s philosophy of science, Radical Behaviorism, took a while to solidify. Years of experimentation and writing. (His dream to become a writer came true though. Check out this bibliography.)

His first major publication was his book, The Behavior of Organisms (1938), but it took him until about 1945 to intellectually stick it to the rest of psychology — which he did in his seminal paper (originally a speech delivered to a group of prominent psychologists) called, The Operational Analysis of Psychological Terms (1945). It was the first time he called psychology out and called for a return to natural science. Few listened.

I sometimes wonder if he would’ve reached more people had it said it more plainly:

“Listen up, people. Every science has underlying assumptions. Let’s start with some basic assumptions here, for the study of psychology — what organisms do, say, think, and feel. If we can’t get on the same page, we don’t belong in the same discipline.”

Alas! Skinner didn’t say anything plainly. Ever. So, to spare you the heavy words of a great intellectual (yes, I hear how that sounds), here are my layperson-friendly descriptions of the philosophical underpinnings of B.F. Skinner’s Radical Behaviorism.

Underlying Assumptions, or Philosophical Tenets, of Radical Behaviorism

Monism: Let’s assume everything about our experience and the expressions thereof — the doing, saying, thinking, and feeling — is of the same “stuff,” caused by the same kinds of variables. No need to posit that our “inner word” is a product of special conditions or causes — it’s simply a matter of observation (or not) by others.

Empiricism: Let’s assume everything worth knowing is observable, measurable, testable. Science progresses through experimentation, replication, and generalization to new situations, not hunches and good intentions.

Parsimony: Let’s assume the explanation that requires the fewest assumptions is preferable over those that make many untestable assumptions.

Skepticism: Let’s assume we will always be progressing science, learning new things that either strengthen what is already known or blow it out of the water. Let’s leave room for discovering new phenomena, without throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

Pragmatism: Let’s assume that what matters most in science is not only how well discoveries explain phenomena but also that they work — they help us predict, influence, or make sense of behavior so that we can improve upon it. If not — if the explanation leads to a dead-end inside a person, like consciousness, self-esteem, willpower or, yes, “the brain,” broadly — even the most intuitive, elegant-sounding explanations don’t deserve a seat at the table.

Contextualism: Let’s assume behavior (do-say-think-feels) only makes sense in context. A laugh at a funeral is not the same as a laugh at a comedy show, even if the topography looks identical. The “when,” “where,” and “what’s going on around it” — and “what happened historically, in similar situations” — are inseparable from the behavior itself.

Selectionism: Let’s assume that behavior changes for the same basic reason species evolve: the environment selects what works. Behavior that is reinforced sticks around; that which isn’t fades away.

Make sense? I thought I’d launch into more detail about each philosophical tenet in upcoming posts. Maybe give some real world examples? Not quite sure yet. Feedback appreciated, even if you don’t know where I’m going or could go.

Would anyone be interested in video content or “lives” to discuss this stuff?

More Resources

Video

If you’re curious about the word “radical” — meant as “thoroughgoing” — or if you simply prefer to learn through video, check this video out, from my friend, Ryan O’Donnell, The Daily BA. He has more videos, and I recommend them!

Books

Technical readers may want to try Mecca Chiesa or William Baum ‘s introductory books.

Non-technical readers might enjoy the pop-psychology journalism of Amy Sutherland.

Of course, no one’s words are a substitute for those of B.F. Skinner himself. Many of his books are available for free or your named price at the linked site, the B.F. Skinner Foundation.

Thanks for reading and being curious about behaviorism! I hope you learned something new.

Peace, love, and stimulus control,

Jennifer

Love this! I didn't even know this line of your work existed (thanks, Substack!), so will dive into the other chapters soon. Very accessible style, maybe the best I've seen at communicating such subtle ideas in everyday language. More of this, please!